By Brianna Valleskey Brand marketing is, in fact, very measurable. (And if you have any about this, check out part 1 of this series). But once you know what metrics you can measure for brand campaigns, which ones should you focus on? How do you measure your overall brand awareness? And what KPIs do you show your C-suite? We’re tackling all of that and more in part 2 of this series. So get ready for a fun, strategic, and data-driven ride. Knowing What to Measure (and When) Understanding what metrics you’ll measure to determine success should be an integral part of your brand campaign planning. As you think through what your goal of the campaign is, consider what metrics you want to see move as a result. Ideally, these will be leading indicators on whether you’ll hit your larger, overarching goals for the quarter or the year. For example: If your yearly PR KPI is to own the Share of Voice in organic media placements, then “# of media placements” would be a good campaign-based KPI. If you want to increase the organic web traffic to your website, then “increase in direct/referral web sessions” is where you want to focus (whether you look at the direct traffic or referral traffic will be based on the nature of your campaign: are you expecting visitors to come directly to your website from a podcast or out-of-home advertisement, or will they come to your website via referral from another web domain?) The number of metrics you choose to look at should correlate with the size of your campaign. A small- or medium-sized campaign with only a few activities targeted at one channel may only need one metric in order to determine whether or not you are successful. But a larger, integrated campaign with multiple activities going out across different channels will require that you measure multiple metrics. Which metrics though? Generally, if your campaign is primarily brand-focused, then I would recommend focusing on one primary brand metric and two or three secondary metrics. If you’re trying to measure the brand part of an integrated campaign, however, then you probably only need to look at two or three brand metrics maximum. (We’ll address the dangers of over-measuring later in this piece). The length of time you continue to measure a campaign should also be based on its size and the amount that you invested (time, effort, money, etc.) in building it. Small campaigns can usually be measured in a matter of weeks, medium campaigns can go on for up to three months, and large campaigns can be measured anywhere between 6 to 12 months after launch. Brand KPIs for Your Leadership and C-Suite So we know that your executive leadership team is busy, and it’s not helpful for anyone to get them too bogged down in the weeds—especially when it comes to metrics. I’ve listed a lot of metrics in both parts of this series, but keep it simple for your leadership team. Pick three to five metrics that align the most with your primary brand awareness strategies and OKRs. Let me repeat: The metrics you select must align with your OKRs or stated goals for the year or the quarter. Otherwise, you’re just presenting numbers that will confuse and overwhelm your audience. What those three metrics are will vary depending on your company stage, industry, and go-to-market approach. A healthy mix for a B2B SaaS company, for example, could look something like this …

I would use something like this as an overarching reporting framework, with campaigns metrics and what I call “milestone metrics” mixed in: when you pass 100,000 email subscribers, social media followers, daily website visitors, etc. But Are You Gaining Brand Momentum? When trying to build a brand, there are a few qualitative signals you can look at, as well, to understand whether or not you’re gaining traction:

Sure, brand surveys are a little old school, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t use it. Conduct your own survey with SurveyMonkey or Typeform to send to a segment of your market asking how aware of your company they are, how aware of your products or services they are, etc. Or you can partner with a third party service. You’ve probably seen a lot of these on Youtube asking things like, “Which of the following brands have you heard of or seen lately?” with multiple choice answers that are generally two leaders in a space and two newcomers. These are more often used for B2C brands, but can also be an effective way to measure brand in B2B. Tools, Tips, and a Tiny Bit of Parting Wisdom A Quick Word on Tools Some of your brand metrics can be measured manually, while others will likely require a specialized too. Meltwater is great for measuring PR Share of Voice (but you can track that manually by simply setting up Google Alerts and tallying placements in a spreadsheet). SEMrush and Ahrefs are great for SEO share of voice or simply your own keyword rankings. Check out Google Search Console for branded search volume and Google Analytics for all web traffic, which can be broken down by acquisition type (organic, paid, referral, etc.), site behavior, and so much more. Hootsuite and Sprout Social are great social media tools. Salesforce has a social media tool that can make it easier to connect your social activity with the customers in your CRM, but it’s pretty intricate (and, of course, expensive), so not a tool I would recommend until you have a dedicated social media manager on your team. You can also use a tool like the Shield App that has an “earned media calculator,” which quantifies how much you would have to pay to get the same reach as you’re getting with your social media activity. Most of what I’ve mentioned above is related to digital campaigns, but there are a lot of tools to help you connect online and offline marketing. Direct mail campaigns can utilize a custom CTA that takes people to a dedicated landing page just for the recipients (a tool like Sendoso may also help with the tracking here). You can use that same strategy for something like a print ad or billboard. Or if the CTA in any of those places is to call a phone number, you can use intelligent call tracking solutions like ringDNA. One Tip to Rule Them All Are you ready for it? Not all metrics are created equal. No sir. I know I’ve delineated between campaign metrics and C-level metrics already, but here’s a quick breakdown of different levels of metrics that sums much of these two essays up:

But there’s one more thing you should know … A Tiny Bit of Parting Wisdom Just because you can be measuring all of these brand awareness metrics, doesn’t mean you should. I see a lot of teams become strangers to strategy by focusing on all the metrics they’re trying to influence and measure. There is no one-size-fits all approach. Every brand strategy is different. A good place to start is to pick three channels you’re going to focus on, and no more than two metrics for a channel. But learn and iterate and grow to figure out how you can best use your metrics to drive growth, not just measure it. What doesn’t get measured doesn’t get managed — this is true. But what is over-measured becomes unmanageable. So find the right balance of focusing on metrics that work for you, not the other way around. Godspeed, and happy branding!

0 Comments

By Brianna Valleskey What’s your favorite misconception about B2B marketing? I have a few. B2B Marketing Myth: Brand Doesn’t Matter First, that brand doesn’t matter because we’re in B2B—which is, of course, untrue because even in B2B your buyers are still human beings, not soulless corporate entities. Emotions and homo sapien psychology play a part in our purchasing decisions. Take the mere-exposure effect, for example (also sometimes called “the familiarity principle”): a fascinating psychological phenomenon where people develop a preference for things simply because they are familiar with them. Building a brand and driving awareness for it lets potential buyers know that you exist. Remarkable brands ensure that people remember what you do, how you’re different, and why you matter. And the more people are exposed to your brand, the more they’ll like it. Science! B2B Marketing Myth: Brand Isn’t Data-Driven There’s also the misconception that brand marketing is this purely creative endeavor powered by random acts of artistry. And that’s not true either. Brand building is a very strategic and data-driven undertaking. Any question you have about brand can be answered with data. What kind of brand should you build? Start by interviewing your team members. What do they value? What sort of traits or ideas do they want to convey? True branding is your company’s identity authentically expressed. Then look at your target market. Gather qualitative data on what brands they gravitate toward, beliefs they hold about themselves and their work, and the values they look for in vendors they work with. So, now you have a brand. Great. But how do you know if it’s working? There’s data for that, as well, my friend. Which brings me to … My Favorite Myth: You Can’t Measure Brand The biggest misconception around brand building, by far, in my opinion, is that you cannot measure brand. And that is simply not the case. Sure, quantifying your brand’s effectiveness and ROI is not as easy to measure as demand generation or lifecycle marketing. You won’t be able to reach a 1:1 correlation of exactly how much revenue you brought in from one very specific PR initiative. But the truth is that you simply cannot quantify every revenue-driving activity. What’s the dollar value of an email or a phone call from your sales rep? You don’t know. But you know whether they’re hitting quota or not, and you can look at other metrics to figure out if emails, phone calls, LinkedIn messages, etc. are effective. The same is true for your brand. So how do you actually measure brand marketing? Dear reader, I’m glad you asked. I’ll cover metrics for your brand campaigns in part 1 of this series, and then measurements of your overall brand effectiveness plus KPIs to show your C-suite in part 2. Ready? Let’s dive in. How to (Actually) Measuring Brand Campaigns For the sake of keeping this article a (somewhat) reasonable length, I’m going to focus our campaign metrics on three specific owned and earned media channels: PR, social media, and SEO. Are you relating to your public? An effective way to get noticed and build awareness is with PR. But once you’ve announced your round of funding, new product, proprietary data, or strategic initiative, how do you know if it’s reaching your audience? Newswire services often give you a “visibility report” with metrics on your press release like total reach, PR pickups, etc. And while there may be some schools of thought that disagree with me on this, I don’t believe those metrics actually matter. Those press release metrics are looking at the number of publications that have automatically published your press release on their website. I don’t know about you, but the last time I checked, your potential buyers and not digging through Yahoo News trying to find your press release. You should still put out a press release—each of those pickups gives your website a little SEO lift with that backlink, and when someone puts your company in a search engine, it never hurts to have Google automatically pull up a recent news hit. But ultimately what you want to be measuring here is placements: How many publications picked up your news release and actually wrote something about it themselves? And it doesn’t always need to be (and certainly won’t always be) a tier 1 Wall Street Journal or New York Times pickup. Pickups in tier 2 outlets and trade publications are valuable. The goal here is to get pickups that occurred because of your campaign initiative. Did you see a week over week, month over month, or quarter over quarter increase in your overall total earned media placements that you can correlate with the campaign? That’s great! Those changes demonstrate a correlation between your efforts and the public’s appetite to learn more about your brand. If you really want to get into the data (which you should, because it’s informative and awesome) — go into Google Analytics and see how much referral traffic came to your website from those placements. Or better yet? See if you can use a marketing automation tool like Marketo to track form fills that landed on your website from the URLs of your PR placements. The real secret to measuring your PR campaigns, though, is to tie them to demand generation campaigns as much as possible. This is less about your ongoing PR program and more about specific “lightning strike” moments. For example, take a recent industry report you released and pitch it to some relevant publications. Then you can measure the number of placements you received in addition to content downloads through your website (and, if you’ve got a solid attribution model, the pipeline and revenue influenced by that content). How social is your media? Your social media campaign doesn’t have to go viral for you to see meaningful results. I’ll say it again for the people in the back: You don’t have to go viral for something to be successful! To understand the performance of your social media campaigns, you can focus on content consumption, organic mentions, and engagement. “Impressions” generally just measures the number of people who saw your post, but in the age of scrolling content consumption, I find it hard to trust a metric that is measuring something that “could” have been viewed. So instead, look at metrics like the number of video views. LinkedIn waits three seconds before counting a view, which, in my mind, is enough to at least leave an impression. Trigger that part of the brain that’s like, “Santa! I know him!” Another great metric to look at is organic employee posts and mentions. Social media channels, of course, want companies to buy ads. So organic posts from company pages are generally de-prioritized in your newsfeed. But posts from your employees, your advisors, your buyers, and customers are not. Targeting them to promote any brand campaigns can be especially effective. (And while you may have to manually track the results via a spreadsheet, which I have done many times, you can tell people to either tag your company or use a specific hashtag so that it’s easier for you to find and track those posts). The last metric I like to look at for social media campaigns is the number of engagements. By engagement, I mean any action taken: like, comment, retweet, and so on. And if your company is big enough to have a dedicated social media manager, I also recommend using social listening tools to track organic brand mentions. And then if you have a really revenue-focused team, which I feel like most companies are moving toward, you can utilize UTM tracking in order to do attribution for pipeline sourced or influenced by people who clicked on links from your social media posts that took them to the website from a specific social media campaign. Where are you optimizing your presence? A good overall brand awareness “health metric” metric is web traffic: How many people are coming to your website directly, from organic search engine results, or via referral traffic? Your website is your digital storefront after all, and you want to be looking at how many people are coming through the door. Mainly, you want to look at all traffic that’s not paid traffic. (You can look at who’s coming through by way of social channels, but I find the UTM tracking that we covered in the previous section to be a more reliable method.) (Side note: I have heard some people argue that organic traffic is a vanity metric to look at, and that is true if your goal is to measure demand generation and pipeline. But this is brand awareness we’re talking about here! People who don’t fill out a form on your website might become a customer in a year, in their next role, or indirectly by mentioning your brand to a colleague or coworker. Don’t get so caught up in trying to solve for everything with a single metric that you end up measuring nothing.) Another metric to look at in the realm of search engine optimization is branded search volume, which can show you how many people are actually searching for your company. (Google Search Console is your friend here.) From a competitive standpoint, you can even look at your SEO Share of Voice on page on search results vs. your competitors: Of the keywords you want to rank for, how many are you ranking above your competitors for? And finally, if you really want to impress your leadership team (which I am, of course, here to help you do), you can calculate the equivalent CPC value of your organic search rankings (basically the amount of money you’re not having to spend on paid search results). But, That’s So Many Brand Metrics! I know. Take a deep breath. The good news is that you do not — and should not — be measuring every single one of these metrics for every single one of your campaigns. I’ll go into more detail about how to decide when to measure which metrics (and the tools you can use to do so), along with how to measure your overall brand effectiveness and KPIs to show your C-suite in part 2 of this series. In the meantime, you should start debunking your own favorite B2B marketing myths. Challenge conventional wisdom! I dare you.  The best marketing teams know when to throw punches and when to roll with them. The best marketing teams know when to throw punches and when to roll with them. By Brianna Valleskey Our marketing agility has been tested as of late. COVID-19 stripped away core components of business strategies across the globe, forcing us to face the weight of unprecedented change; a new world where business travel and in-person events are replaced by remote work and budget cuts (for both us and our customers). Our strategies were hit with an asteroid. Overnight, our ecosystems changed. Most of the mass extinction events on earth have been due in some way or another to global warming—with as much as 75% of all life on earth disappearing in a single episode. In a changing environment, you either collapse or adapt. Nothing is as costly as inaction. Adaptation vs. the Fear of Change In nature, adaptation is the process of a species becoming fit to live successfully in its current environment. Nature is very budget-conscious; it can’t afford to simply let life in an ecosystem die out when things change. Biological forces are always working to maximize the return on nature’s investments in living things, so adaptation is a natural reaction to an evolving ecosystem. Marketing agility means successfully adapting to new (and continuously evolving) environments. It’s the ability to adjust your marketing programs quickly and easily based on often unforeseen circumstances related to your company, your customers, or something else in your ecosystem. This isn’t a foreign concept to marketers. We’re constantly making changes based on different criteria like timeframe, data, or engagement. But in this case, I’m talking about dealing with seismic shifts: tectonic plates moving inches at a time below the surface that form a richter-breaking earthquake. Having the marketing agility to maneuver massive change not only rescues you in dire situations, but it helps you execute more effectively on day-to-day changes. Fear of the unknown is very real. When something unprecedented happens, no one wants to just throw away a go-to-market approach that has worked for 24 months straight without another surefire plan in place. But we must come face-to-face with that fear in times like these, when our families, our companies, and our customers depend on us. We must be brave enough to stop for a moment and take stock of the current situation in order to determine the best course of action moving forward—whether or not that means abandoning programs we spent 18 months trying to build. You never have to throw anything away, of course, as long as it continues to drive measurable results. But keep a close eye on it, and at the same time proactively research your new environment and test some new things based on what you learn. Utilize adaptive storytelling. On Relevance Stories build our identity. They help us understand the world, and they shape the way we see it. In business, we tell stories with our brand design and messaging, through our events and experiences, via the content and communications we share, in the sales and customer conversations we have, and so much more. We’re telling stories constantly to help people understand why our product or service is relevant to them. What we say in those stories must be relevant to our audience—not ourselves. The messages you bring to the market must answer the question of why you’re reaching out to that audience (whether on a one-to-one or one-to-many basis) and why they should care. Otherwise, you’re a stranger with a sales pitch or a glazed-over digital ad. If a brand is the sum of all interactions someone has with your company, then your collective go-to-market message is the conversation you’re having with your audience. Are you talking about you or about them? Hopefully, your core narrative and messaging framework are, indeed, relevant to your audience. You solve a challenge, satiate a desire, or provide something else valuable enough for people to invest. And that value is something that’s relevant to each and every individual in your audience. It's what ties them all together in a common thread. “Personalization” is for building relationships with individuals. Relevance is for building relationships with the masses. PSA: Call Your Customer Relevance ensures that the way you communicate your value speaks to what matters most to your audience today. Your core message might resonate with your audience on an overall basis, but if it’s not among the, say, three-to-five top things they are thinking about prioritizing within the next week/month/year then they’ll scroll right past you. In the attention economy—where scarcity exists not in the amount of space we can use to get in front of our buyers, but in the length that we can hold someone’s interest—being relevant means staying close to our buyers and customers. We hold someone’s attention by bringing valuable information as a resource, answering their questions, and helping them make informed decisions. But the world changes quickly. What mattered to many of us two months ago isn’t even a blip on the radar anymore. And that can happen to our buyers or our customers on any scale (big or small) at any moment, whether or not we know it. We must always know how to make our core value and messaging hyper-relevant to what matters most to our audience today; this month; this quarter; this year. If we can’t speak to that, then maybe we need to rethink what we’re doing. This approach, of course, requires staying very close to your audience. Listening, conversing, interviewing your customers as much as possible. As marketers, we spend so much time reading about them and writing for them and talking about them, but we don’t often get the same amount or frequency of face time as some of our other customer-facing counterparts. This is the part where I tell you, The Marketer, to call your customer. Living, Breathing Stories Of course, many of us in the marketing discipline do already call our customers. We interview them for case studies and put them on our advisory boards and ask for product feedback. But what I’m suggesting is just a regular cadence of check-ins just to understand what’s top-of-mind for them. It’s not a sales call, but rather a way to understand how they’re thinking on a day-to-day basis, throughout different times of the year, and during unique events. What decisions are they considering and when (and why)? Thank them for taking the time to speak with you with a coffee or cocktail. (Alternatively, you could send them a handwritten note or another token of appreciation if you don’t live in the same region.) Cycle through interviews with different customers to ensure you’re getting a diversity of perspectives. Keep the questions short (don’t exhaust your interviewees) and focus on getting into their state of mind to be the best resource possible. Find out …

At the same time, be sure to establish a strong pipeline of feedback from your sales, support, and other customer-facing teams. Use the same set of questions with these internal teams and compare that research to yours. Find the patterns. Then craft a mini messaging framework that aligns with your core framework but is hyper-focused on where your audience’s head is at right now. As a situation changes or time goes on, allow that messaging framework to evolve. Even something as small as a change in certain vernacular should or a specific emphasis should be allowed to inform you’re saying to the market. Use continual research in order to make educated guesses on where to iterate. Let your stories live and breathe. “Brand journalism” is one of those murky terms that typically has to do with sharing stories about a brand to build affinity; and it usually involves some combination of public relations, content, and corporate communications. What I’m describing here is more like ... adaptive storytelling, where you know the story but you allow it to grow and adapt to the situation as necessary. This allows you to be a lighthouse to your buyers, customers, and community when they’re navigating uncertain waters; a reliable and trustworthy safe harbor. Tone-deaf messages without relevance (and in uncertain times, hyper-relevance) fall on disinterested ears. Winning brands build relationships like people do: by creating mutual value, through shared positive experiences, and being there in times of need. This piece is part 1 in a series about marketing agility. To read part 2, click here.

By Brianna Valleskey

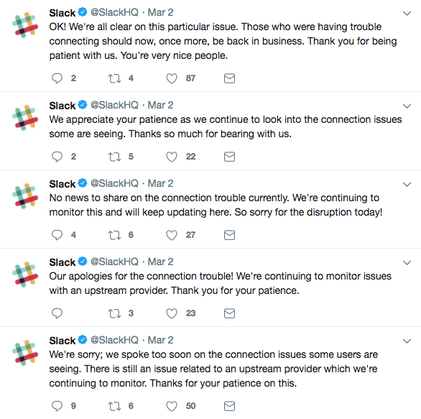

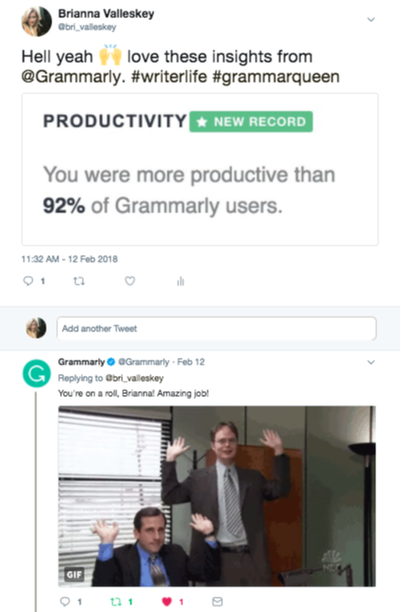

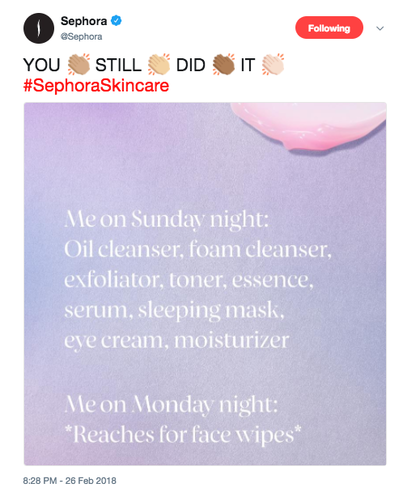

Why do some ads go viral? And why are others so easy to forget? I started thinking about this after Nike’s “Dream Crazy” advertisement came out a few months ago. The video features former NFL player Colin Kaepernick, whom people love or love to hate. You could argue that the video’s 27 million views are because Nike decided to feature Kaepernick in an ad, but the controversy was just a hook. A much more real story lies at the heart. If you haven't seen it, the video plays motivational music while showing people of every gender, race, religion, and economic status pursue their dreams in spite of societal standards: A child without legs in a wrestling match. A Muslim woman boxing. A homecoming queen who’s also a linebacker. An NFL player with only one hand. A professional tennis player from Compton. “If people say your dreams are crazy—if they laugh at what you think you can do—good,” says an identified narrator. “Stay that way. Because what nonbelievers fail to understand is that calling a dream crazy isn’t an insult. It’s a compliment.” Damn. That’s something I can really feel. And I’m sure I’m not the only one. Having a “crazy” dream is something I think everyone has experienced at least once in their lives. And then there was the #LikeAGirl campaign from Always, where young women and little girls explaining what it means to run “like a girl.” While the teenagers acted like damsels in distress, the girls ran their adorable little hearts out. It’s a sweet but sad reminder of how society warps the way girls see themselves as they grow up. That video has 66 million views. Two very different commercials. Same effect. So what’s the secret ingredient? Stories. They're our way of making sense of the world. “When people read a book, watch a movie or hear a story, regardless of medium or format, it is imperative that they see themselves in the story,” write SapientNitro executives Gastron Legorburu and Darren McColl in “Storyscaping.” These stories are so powerful because they tap into something that millions of people have personally experienced. The story in the ad becomes our story (and vice versa). And this has been the case for thousands of years. From Cave Paintings to Kaepernick Of course, modern marketers were not the first storytellers. Cave paintings dating as far back as 40,000 thousand years ago inform us that our ancestors felt the urge to express their experience. “Whether it’s Neanderthal elbow rubbing or social media socializing, story is central to what it means to be human,” write Legorburu and McColl. Perhaps this can, in part, explain why the same stories appear across space, time, and culture. “Every culture has a flood story about how the whole earth was flooded and things started over,” says mythologist John Bucher on an episode of Ologies. “Stories of floods predated Hebrew scripture, [from] Amazonian culture, Greek culture, Roman culture, Asian culture.” Stories are the driving force behind the history we learn, the religion we practice, the government we follow, the beliefs we hold, the people we love, and even the way we think about ourselves. Studies show that reframing your narrative can yield a more positive identity. And yes, gamification of social media platforms makes them incredibly addictive. But there’s more to it: What other medium gives people complete and utter control over how others see their story? Not to mention the ability to voraciously consume stories about others. Legorburu and McColl again: “Humans have an innate ability to take disparate events and connect them together to create meaning.” To tell stories is to be human. But why is it that the marketers at Nike and Always and other world-dominating brands can use stories to awaken our hearts and, consequently, open our wallets? This is Your Brain on Stories Long before Joseph Campbell and “The Hero’s Tale” helped George Lucas produce the most well-known space opera of all time, Aristotle taught us that every story should have a beginning, middle, and end. This three-act structure is important, mythologist John Bucher explains, because the way storytelling structure works actually mirrors the way the human brain solves a problem. 1. A goal or yearning is introduced, but conflicts and/or obstacles arise. This goes even further. “Storytelling evokes a strong neurological response,” writes Harrison Monrath in a Harvard Business Review article. He goes on to say that research from Neuroeconomist Paul Zak shows how our brains produce cortisol (the stress hormone) during tense moments in a story, while sweet/cute/etc. elements of a story can cause our brains to elicit oxytocin (a chemical that makes us feel good). What’s more? A happy ending can trigger the release of dopamine in our limbic system, making us feel hopeful and optimistic. Zak, himself, writes in another Harvard Business Review article that these findings are relevant to business settings. “For example, my experiments show that character-driven stories with emotional content result in a better understanding of the key points a speaker wishes to make and enable better recall of these points weeks later,” Zak writes. The advertisements from Nike (Dream Crazy) and Always (#LikeAGirl) are character-driven. For Nike, the character is the underdog. With Always, it’s adolescent girls. But there’s another element still that makes them so powerful. “The most successful storytellers often focus listeners’ minds on a single important idea and they take no longer than a 30-second Super Bowl spot to forge an emotional connection,” Monrath writes. This, my dear readers, is key. Stories are Shared Experiences What’s the one word, phrase, idea, or vision you want your audience to walk away with? And how will you get that across before you lose their attention? Nike doesn’t just want you to dream big. It wants you to dream crazy. And Always wants women and girls everywhere to know that “like a girl” is not an insult. Neither of these things has anything to do with the products Nike and Always sell. Yet, Always saw a higher-than-average lift in brand preference after the #LikeAGirl ad, where purchase intent grew by more than 50%. And Nike experienced a 31% increase in online sales following the release of its Dream Crazy spot. So what does this all mean? The best marketing isn't marketing at all—it's storytelling. Authentic, emotional, and character-driven stories stimulate our brains and saturate our hearts. Stories trigger the most important brand message of all: You belong. Everything else is posturing.  By Brianna Valleskey There’s sizeable obsession around the idea of making a brand seem more human right now. A quick Google search yields at least 10 pages (yes, TEN. I stopped looking after that) articles touting tips and tricks to make your brand sound/look/feel/act more human. It makes sense. People buy from people (and brands) they know and trust. Even in the realm of business, Maya Angelou’s famously poetic quote about relationships rings true: “People will forget what you said. People will forget what you did. But people will never forget how you made them feel.” Purchasing decisions, like most decisions, are made based on emotion. So, if you can create at association between your brand and positive feelings (beauty, strength, safety, warmth, excitement, sexiness, etc.) in the minds of consumers, you’ve struck gold. And the quickest way to do that by talking to them directly through social media. But I think what we need to remember is that a business is not a human - it’s a tribe of humans all working toward the same goal. And that’s the image that should be reflected in your brand messaging. The issue arises when brands become fixated with the idea of appearing human. In their attempt to appear more authentic, they come off as less genuine. I’ve seen some instances so cringe-worthy that it was like watching your Baby Boomer father try to be cool by saying something is “on fleek.” For what it’s worth: I give the businesses that are trying to be human more credit than the ones who use social media as another channel for self-promotion or simply a glorified RSS feed for their blog. I think what we need to remember is that a business is not a human—it’s a tribe of humans all working toward the same goal. And that’s the image that should be reflected in your brand messaging. The big problem with making brands more human is that, in doing so, many companies make them LESS human. But it doesn't have to be that way. As helpful as high-level strategic advice can be, I also want to provide some practical examples of what I mean. Here are some companies doing it well across a few different industries (for the purposes of this article, we’ll mostly focus on their Twitter presence): Slack (@SlackHQ): B2B Tech Slack knows that a brand is the sum of all the interactions people have with your company. That’s why the organization responds to almost every single tweet directed at their Twitter account (in the early days, especially, thousands of those replies came from Slack’s own CEO, Stewart Butterfield). The company is also super transparent and proactive about updating customers on support issues. Six million people use their platform every day, and they keep everyone up-to-date via both their Twitter account and Slack System Status page. The best part? They always sound super approachable and down to earth when communicating to their users. Also, have you heard of #beeftweets? It’s an internal Slack channel the company uses to draw attention to customer complaints on Twitter related to product issues, feedback, feature requests, potential improvements, etc. The Slack team discusses how to address the issue. If a fix is in order, it’s launched within a couple of days (as the complaints are typically minor). Then Slack tried to respond to the original complaint on Twitter to let the user know that they made the fix. I can’t think of a better way to make your customers feel heard, understood and appreciated. Grammarly (@Grammarly): B2C Tech Grammarly really, really understands their audience: millennial (or at least tech-savvy) people who want to write well. They use their Twitter profile to inspiring #MondayMotivation quotes or funny #FridayFeeling memes, but also to share helpful spelling, grammar and punctuation tips and tricks. Another wonderful trait about Grammarly is that the company immediately responds to people who tweet at them. I’ve posted a few times about the weekly writing stats they email out, and they always respond with a fun, encouraging message that legit makes me want to be friends with them. Seriously, does it get any better than a meme from “The Office”? I think not. Sephora (@Sephora): Retail Sephora acts like your bright, sassy, funny and fun BFF on social media. (That branding is consistent across all of their platforms, as well. The login portal of their website says, “Hi, Beautiful.”) The company uses tons of emojis and their own branded hashtags (#SephoraSkincare), in addition to posting content that’s super relatable to their audience. This is the kind of stuff that makes your customers think, “Yeah, that company really gets me.” Also, instead of merely pushing their products, Sephora provide helpful beauty tips and tricks. They also polls to let their customers chime and celebrate holidays that aren’t specifically related to what the company does. Celebrating is just human nature. DiGiorno (@DiGiorno): Food & Beverage I want to meet the person who runs the official DiGiorno Twitter account and shake their hand. It’s seriously so funny. And not just once-in-while-while-gem-of-a-tweet kind of funny; I’m talking consistently, habitually hilarious. I’d also like to note that the vast majority of the content coming from their Twitter account is simply comical content. The rarely publish adds. Seriously! I counted the company’s 50 most recent tweets and only three of them were ads. That’s only 6 percent of the social media posts on their account! My hypothesis is that it’s a strong sense of self-awareness that their ad message is already pretty well known (it’s not delivery, etc.), and the company has found that it’s a better use of their time to simply build brand affinity. Brave, DiGiorno. Your strategy is brilliant. A lot of marketers talk about branding as this abstract, philosophical concept. But I think it’s much simpler than that: consider the people you want to connect with: What do they care about? Where and how do they consume information? How do they communicate? What groups do they want to be a part of. As Chris Brogan says, “Business is about belonging.” So make your brand simply a tribe of people that your customers (current and potential) would want to be associated with, and they’ll naturally gravitate toward you. And yes, I realize that as a female writer working in tech who f*cking loves pizza, these are all brands I personally love. But there are plenty other examples out there that I’m sure I’ve missed. Do you have any favorites? Let me know in the comments below!

By: Brianna Valleskey

How do we develop more creativity in our organizations? Most people think of creativity fairly narrowly and only in terms of art or science, but Ed Catmull believes otherwise. “Creativity is the process by which we solve problems,” said the president of Pixar Animation Studios, “whether that’s through a story, marketing or a relationships between partners and customers.” Ed is a 20-year veteran of Pixar, as well as the author of “Creativity, Inc.” His ideas challenge conventional wisdom about the creative process, and he was kind enough to share some important creativity hacks during his INBOUND session last week. I thought they were more than worthy of a dedicated blog post. Ed Catmull’s Advice for Empowering Creative Thinking Increasing creativity means removing roadblocks. People often ask how someone can be more creative. Ed said that a better question is, “What management, cultural and other roadblocks are getting in front of being creative?" By the time Disney purchased Pixar in 2006, it hadn’t produced a major box office hit since “The Lion King” more than a decade earlier. The studio suffered from a lack of introspection, Ed explained. Different organizational groups (marketing, finance, technical, filmmakers, etc.) within the company had different values ― as they should ― but the values of the production team prevailed. While production, itself, was optimized, that structure forced much of the creative strategies to fail. That forced alignment around the values of the production teams acted as a roadblock for the studio’s creativity. To help solve this problem, the studio leadership (including Ed, Steve Jobs and John Lassiter) created a “story trust” (more on that below) for the Disney team to help prioritize creative values and reinvigorate the team’s process. A few years after that, Disney finally produced its next box office smash, “Tangled.” Ego is a creativity blocker. Another secret to increasing organizational creativity is to remove ego from the process. The idea for Disney’s story trust came from Pixar’s own “brain trust,” a group that comes together after the first screening of a new film. They trust operates on a few very specific principles: It’s peer to peer. Filmmaker to filmmaker. The purpose is to remove management and hierarchy from the room so that the director can make decisions; not Ed or (Pixar Chief Creative Officer) John Lasseter. The filmmakers are expected to give and listen to honest notes. Removing perceived oversight allows directors to actually hear what people have to say. Another principle of the brain trust is to carefully observe the filmmaker dynamics: Does everyone contribute? Does somebody dominate? Are they trying to help each other? Is someone afraid to speak? Of course, the brain trust doesn’t function perfectly. But when it does, Ed said, magic happens. “And by magic, I mean that you feel ego leave the room,” he said. “All the attention is on the problem.” This is important. Removing ego allows ideas come and go without people becoming attached to them, thus enabling the creative process to flow. New ideas are fragile. Treat them as such. Ed claims that all Pixar movies suck at first. “I don’t mean that because we’re being modest or self-effacing. I mean that in the sense that they suck,” he said with a chuckle. The first version of “Up,” for example, involved a castle floating in the sky. A king lived there with his two sons, and the people in the castle were at war with the people on the ground. The sons didn’t like each other very much. They somehow go overboard and end up on the ground (in enemy territory), and then come across a large bird. According to Ed, this version sucked. The only thing that came from it was the bird and the word “up.” The second version had a 20-minute intro. Carl floats away in the house with a boy scout. They land on a lost Russian dirigible that’s painted underneath to look like clowns. That version didn’t work, either. The fourth version brought back the large bird and introduced the films main antagonist, Charles Muntz. The main plot driver, however, was that the bird’s eggs gave everlasting life to anyone who ate them (which is what Muntz was after). The film still wasn’t working. They lost the eggs, whittled down the 20-minute prologue to four and a half minutes of pure gold and produced one of the most-beloved animated movies of all time. (Admit it: That intro made you tear up.) “This path [of that film] was wildly unpredictable,” Ed said. “New ideas are often fragile and off track. We had to protect that crew while they working on something that wasn’t good, trusting that their motivations were going after the right thing.” Don’t be afraid of the wilderness. Ed Catmull probably knew Steve Jobs better than almost anybody else. After he left Apple, Steve purchased the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm (where Ed worked) in 1986 and renamed it “Pixar.” He was also running NeXT computer at the time. Ed watched Steve experience countless failures during this time, but he also watched him learn an incredible amount. Steve’s empathy changed dramatically over that time, Ed said, enabling him to become the person who returned to Apple and made it great. “This was a lot like the hero’s journey,” Ed said, “where the hero is cast out of the kingdom, wanders in the wilderness, learns and lot and then returns to make the kingdom a better place.” The hero’s journey refers a classical story arc, and some of our favorite tales follow this template: Star Wars, Harry Potter, The Hobbit, The Wizard of Oz and even The Princess Bride. Ed’s point here is to not be afraid to go into the wilderness (or wander or get lost or attempt something that seems impossible), as it almost always ends up being a period of immense growth. Believe that what you’re doing makes a difference. Ed’s final piece of advice for fostering more creativity in our organizations was simple: put purpose behind everything you do. “If you believe, as I do, that your actions make a difference, this means you can modify your reality. You can change the future,” He said, adding that he hoped everyone in the audience would do so. From all of this, I think we can definitively say that enabling creativity is critical to the future success of any company. I challenge all business leaders to let creativity run wild within their organizations ― to infinity and beyond. P.S. Ed started his session by saying that Pixar does not make movies for children. The studio makes movies that are intended for adults (but still accessible to everyone). People forget that children live in an adult world, he said, and they’re built for figuring things out. They want to figure things out, and that process of figuring things out is also creative. I found this incredibly clever. See below for a few books that specifically tackle the topic of creativity.  By: Brianna Valleskey The first thing you need to understand about Bozoma Saint John is that she is a total badass. Not only was she the first woman ever to speak at Apple’s Worldwide Developer Conference (praise be), but she’s also a brand executive with Ghanaian heritage currently making waves in Silicon Valley. The former Apple Music head of marketing fearlessly took on the role of Chief Brand Officer at Uber earlier this year. The ride-hailing service hit the jackpot with Boz, as she’s definitely the only person on the planet fierce enough to handle that job right now. The second thing you need to understand about Bozoma is that she’s a masterful storyteller. She didn’t walk onstage for her INBOUND presentation. The woman sashayed. Full of swagger and sass. In the age of photo filters and tailored responses, her authenticity was extremely refreshing. And her presentation was on point. “I believe brands are people.” Bozoma’s story started long before she was born. She’s named after her paternal grandmother, who was the fourth wife of the village chief (her grandfather) in a Ghanaian coastal town. As a child, she and her family lived in California, Kenya and Ghana before moving to Colorado. “I was 12, and the last thing on the planet that I wanted to be was different,” Boz said. “But there I was, different: 5 feet 10 inches, long braids, strong Ghanaian accent.” She felt like she didn’t belong, but her classmates were intrigued. They asked innocent, benignly offensive questions like did Ghanaian people sleep in huts? Were monkeys their friends? Had she seen a white person before? What she learned, however, was that it wasn’t the answers to those questions she needed to have ready; but rather, answers to the questions her classmates asked amongst themselves: Was Paula Abdul or Madonna a better dancer? (Paula Abdul). Which football team are we going root for on Sunday? (The Broncos). One particular question has haunted her ever since: “What will I say?” It keeps her up at night. She wanted to say things that make her equal. She wanted to say things that make people sit up, pay attention and give her a chance. Now, she sits in a chief seat in Silicon Valley and wonders what her grandmother would think. “I know I made my grandmother proud when I made a trip to the White House last winter,” she said while showing a picture with her and the Obamas. “Those who have walked this walk before us are so proud to see us standing in this space.” Just as our ancestors’ legacy will forever leave a mark, Bozoma intends to leave a mark. No place will ever be the same once she sashays through it. More importantly, her story demonstrated how her culture shapes her personal brand. “I believe that brands are people,” Boz said. “They have personalities. They have perspectives. They have hopes and dreams and fears and failures.” Without the storyteller’s unique perspective, she added, the story falls flat. In one way or another, each storyteller injects their own excitement, their fear, their purpose into whatever tale they’re telling. “A ride is such an intimate space.” There’s someone/something in each our lives we want to make proud, Bozoma said. What is that for you? What motivates you? It could be people, events or even injustice (#takeaknee). She bet that each person in the entire room could name a brand that holds some sort of meaning to them. Even if that meaning seems irrational, we still believe. “It is the belief that makes us choose that shoe brand over another, that drink over another, that disruptive ride-sharing app over another,” she said with a laugh. “I want to inspire that choice.” Until this point, Boz explained, the brand of Uber has relied on the left side of the brain. The side that is rational, analytical, data driven, factual, objective and literal. But then things changed. Dirty laundry was aired, and people wanted to delete Uber. Suddenly, she explained, the left side of the brain couldn’t make sense of using the app. The right side of the brain, however, is full of emotion. It’s the side that is sorry. It feels bad for wrongs and wants to make them right. It cares more for the human reaction than the mechanical, and Bozoma believes it has been silenced for too long. Uber has 16,000 employees dedicated to the future of technology and making the world a better place. That includes engineers, marketers, service reps and, of course, drivers. “A ride is such an intimate space,” Boz mused. “When you get into a car, you’re a few feet away from a complete stranger.” Some people choose to ride in silence; others engage in conversations that can go literally anywhere. Bozoma often hears drivers say they feel like therapists. People get into the car when they’re feeling sad or angry or anxious, and they talk their feelings out with someone they just met because, sometimes, it’s safer than a close friend. “The chances are so slim. Probably impossible. There’s no math. Only magic.” Long before joining Uber’s team, Bozoma had ordered an Uber Black at South by Southwest. She was terrified when it pulled up. The car looked as if it had been really good at some point, but then went through something terrible: parts had been smashed, the paint was keyed, the carpet was torn. She made a joke about it when she got in the car. Instead of laughing, the driver was embarrassed. Boz asked him what happened. The driver got even more embarrassed as he proceeded to explain that his car had been vandalized by taxi drivers while he was helping a rider get her bags at the airport. The driver began to apologize. He knew he shouldn’t be driving the car like that. But his brother had recently passed, and he wanted to make extra money so he could honor him by seeing their favorite artist perform at SXSW: Iggy Pop. Bozoma gasped. She got goosebumps. At that very moment, she was on her way to have dinner with Iggy Pop. What is the probability of her getting into that car with that person on that very night? “The chances are so slim. Probably impossible. There’s no math. Only magic,” she said. Bozoma doesn’t believe in accidents. She immediately knew they were meant to meet and that the driver should come to dinner with her. She invited him. They both cried. During the meal, she sat in wonder at their fortune while the Uber driver told Iggy Pop his story. She had met a total stranger in a city that wasn’t her home and made a powerful connection that they’ll both remember for the rest of their lives. It all started with an Uber. “It’s important to see ourselves in the stories we tell.” Now that Bozoma works at Uber, people feel inclined to tell her their own stories of using the ride-hailing app. But so much has changed in the way we tell stories about technology. Back in the 1980s, she said, technology was either fantastical or informational. Brands like Levi’s were selling a good time, and technology seemed almost out of reach. She explained that though we talk about a great divide between races and classes in America, technology platforms and products have lessened it (if not eliminated it entirely). “The story we tell about [technology] can’t be cold. It has to be warm, like us. It has to be intimate,” she said. Technology can connect us with other human beings, but what actually connects us to each other? Emotion. Human emotion drives all of our decision-making, Bozoma said. When you hear these stories, it’s her intention to make you feel something positive ― to recall them with inspiration or delight. As a brand marketer, that is her goal. She said that all brand stewards must be authentically themselves when telling their stories. “It’s important to see ourselves in the stories we tell,” she said. “I hope that for each of you, the diversity of our stories will not just be told, but appreciated and celebrated.” Naturally, everyone in the audience left with all the feels (i.e. Bozoma accomplished her goal). She’s high on my list of role models, and I’m looking forward to see her storytelling magic come to life at Uber.

By: Brianna Valleskey

Jen Rubio is my hero. She’s the co-founder of Away, a lifestyle travel brand that makes thoughtfully designed luggage, but also a super sharp entrepreneur, marketer and commerce expert. Jen used to run social media at Warby Parker, where employees would tweet video responses to questions about the product (while wearing Warby Parker glasses, of course) ― a visual branding strategy ahead of its time. So when I found out Jen had a spotlight session at INBOUND this year, I was ridiculously pumped. She spoke about creating a brand with emotional appeal, building a product that actually helps people and marketing to a mass customer base (while also finding ways to specialize). Check out my summary of her insights below. The Principles of Building a Brand People Love 1. Birthing an innovative brand ≠ reinventing a business model. Not every entrepreneur has to reinvent the wheel. Or, as Jen put it, reinvent an existing business model. Warby Parker wasn’t the first business to sell glasses online. Away isn’t the first luggage company. But Jen knows this. How you can differentiate your business, she explained, is by creating an incredible brand that consumers want to interact with. Every brand has an origin story (a founding myth), and Away’s story starts with a piece of broken luggage. Frequent travelers have likely noticed that the same few luggage brands always show up in airports. You assume it’s because those brands make quality luggage. Why else would people buy it, right? Then Jen’s luggage broke. She went online and asked her travel-savvy friends what kind of luggage to get. The answers that came back surprised her: “I don’t know, but don’t get what I have.” Most people had inherited their luggage, received it as some sort of parting gift from a former job, or simply didn’t like it. “There was just no overwhelming sense of brand affinity for luggage,” Jen said. “Travel is something that everyone does. It’s something that excites people. But why wasn’t there a travel brand that people were excited about?” So she set off to make an awesome luggage brand that resonates with people, and for a reasonable price: All of their bags sell for under $300. Similar bags would cost anywhere from $600-900 in retail stores. But part of Away’s mission was to create quality-to-price value. 2. Design intention must equal customer perception. Before creating the first prototype, Away did research. A lot of research. They started by sending out surveys where people were asked to check off the boxes of each feature they wanted in their luggage. All of the boxes would be checked off. When asked which features people wanted to pay for, none of the boxes were checked. So the Away team switched to field research. “I cannot tell you how many hours we spent watching people pack,” She laughed. “We’d visit our friends and extended networks with coffee and bagels simply to watch them pack.” Those hours were worth it. The team uncovered insights that helped them understand what to design for: People don’t like their shoes to touch their clothes. People snatch plastic bags from hotels to store wet clothes and dirty laundry. “People are so used to having a crappy experience packing their luggage. They didn’t know how to describe what they needed,” Jen explained. “We had to witness them doing the act.” Away iterated on their product hundreds of times to create its minimalist design. The more people use it, however, the more they realize why certain features are in place. Take the two zippers on each bag ― they create a distinct set of clicks when you clip them into the (TSA-approved) lock. You get both the satisfaction of a packing job well done, as well as the assurance that the bag is firmly shut. Another part of good design is just making sure that what your design intention is equals the customer’s perception. Away’s luggage is made from polycarbonate (the same material used to make fighter jets), but they wanted the suitcase to have a little give in case it was ever dropped on the ground. So a flexible prototype was made and tested with a focus group. The result? The focus group assumed that the material was cheap and flimsy. “We’re lucky that we had that group,” Jen said. “If we had gone out to the market with that, we couldn’t have been there to explain to every customer the thinking, intention and design behind what they perceive as cheap material.” Those are the tiny details that make people obsessed with the product, Jen said. Customers frequently write in to thank Away for making them better packers. 3. The delta between good design and brand is emotion. Jen loves to travel. She’s been to ~60 countries and all seven continents on the planet. The core of Away, as a company, is to create a beautiful, thoughtfully designed suitcase. But, she explained, you can have things that are beautiful and well-designed, and you still don’t feel a sense of connection with that product or that company. What makes something a brand is the emotional connection you feel with it. “If we can inspire our community of people to look at a map and feel like all of it is in reach, then we’ll have done our job,” Jen said. “I know that seems like a lofty statement for someone who makes a suitcase, but the small things count.” If that’s not creating an emotional connection to a brand, then I don’t know what is. Away’s secret sauce is to mix that emotion with phenomenal design. The brand identity for their luggage is very minimal: clean and simple, but not austere. It’s meant to attract a large market (i.e. people who travel). The company appeals heavily to specific market segments, however, by frequently collaborating with different brands. Away has worked with companies like West Elm and celebs like Rashida Jones to reach new audiences and go all out on various designs. Each collaboration has its own soul and spirit. (As I’m writing this, Away is featuring a gorgeous piece of luggage made in collaboration with Amastan Paris on its website). “It’s easy to say your product targets people between the ages of 16 and 60 who travel, but you probably aren’t going to make anything exciting,” Jen said. As a brand, Away is definitely exciting. But it’s also down to earth. Jen mentioned that Away isn’t meant to be like that person you follow in Instagram who takes all these amazing trips you’ll never be able to afford. Instead, Away is the person who you see travel somewhere and think to yourself, “I’m adding that destination to my list.” 4. Telling people about your product < Demonstrating what it enables them to do. The experience of traveling is the essence Away’s brand. A key part of traveling, your luggage can really make or break a trip. Jen believes that packing and unpacking doesn’t have to be the worst part of it. That’s why Away exists as a travel lifestyle brand that monetizes by selling suitcases. “A lot of luggage brands use their product pages to talk about the tech specs, materials and dimensions,” she said. “We do that, but a large majority of our product page is showing the bag in action: being packed, being stored under your bed, etc.” Away’s store in NoHo (NYC) doesn’t sell luggage. It sells the experience of travel. One corner of the store is dedicated to the suitcase, where shoppers can move it around. Pack it. Play with it. But another corner is a cafe filled with travel books, magazines and city guides. It has shelves filled with things that you bring with you on a trip (like a sleep mask and headphones). “If you’re not telling the story of what your product can enable something to do, then you’re just a company that sells things,” Jen said. “You’re not a brand.” What I loved most about Jen’s approach is how she integrates seamlessly product design with brand storytelling. I’m looking forward to see what Jen and her luggage company do next. You can follower her on Instagram and Twitter at @jennifer. P.S. I hope Jen writes a book someday. In the meantime. here are some great books on branding ...

By: Brianna Valleskey

I work with a lot of small- and medium-sized businesses that all want the same thing: growth. And that’s great! Growing your business means serving more customers, creating new jobs, generating innovation and, of course, increasing the bottom line. But, this is also where I see a lot of companies start to fail. We know that failure is common among small businesses. According to the Small Business Association, about two-thirds of businesses with employees (not sole proprietorships or “solopreneurs”) survive at least two years, and almost half survive at least five years. Often-cited articles from outlets like The New York Times, Forbes and Inc. document the numerous reasons many business fail: dysfunctional management, slow or stagnant cash flow, financial illiteracy, poor value proposition, lack of cash cushion, operational flaws, low demand for the product or service … the list goes on. There are a few areas, however, that I feel like haven’t been discussed at length. These observations come directly from companies I’ve either worked with or worked at, some of which are absolutely killing it. Others, not so much. Here’s what I’ve learned from being on the front lines of multiple SMB companies. 3 Things that will Absolutely Run Your Small Business into the Ground 1. Try to do too many things at once. Successful business growth involves a lot of moving parts, including a well-oiled lead generation funnel, a fluid sales process, strong customer retention and (of course) a strong value proposition for your product or service. The trick is that you can’t perfect all of those things at once. I know of a software company that was constantly struggling to communicate their value prop, while also trying moving upmarket, expand their product and reduce customer churn. The result? They couldn’t do any one of those things well because the company lacked focus. In addition, they lost almost half of their employees ― some were voluntary departures after being overworked; others were laid off due to the company’s poor performance. I also know of a company that has a 98 percent retention rate with high-profile customers like Uber and Paypal. I kid you not. This CEO waited for years to perfect his company’s product and implementation process so he could ensure customer success. If you don’t believe this method works, just look at Slack. The company started building their product in December of 2012, launched a beta version (they called it a “preview release) in May of 2013, and then finally launched to the public in February of 2014. Slack spent 14 months perfecting its product. As a result, its become one of the fastest-growing companies in the market. 2. Undervalue your employees. You can have the best product in the whole world; but if you don’t have good employees to market the product, close deals with the right prospects, serve your valued customers or iterate on the product, you do not have a business. And you will not make money. I won’t even go into the fact that a service business is based entirely on the performance of its employees. Another company I’m familiar with brought in a majority investor that completely changed the company culture. They rid the company of anything that didn’t have to do with business operations, especially anything that resembled “startup culture” (or an immature culture, as I imagine they viewed it). No more autonomy. No more monthly company roundtables. No more team-building events. No more beer Fridays. No more ping pong during office hours. Oh, and office hours were strictly defined as 8-5 or 9-6. The company culture soon became dry and lifeless. People starting leaving. Multiple employees voices their concerns to management, but soon most of the management was leaving, too. The concerns then fell on deaf ears. To my knowledge, they still are. And the business is not doing well. You don’t have to take my word for it. Look at Uber: After blatantly ignoring employee complaints of its employees, the company suffered a public relations disaster of epic proportions when those employees went public with their stories (examples here and here). Some of the companies I work with, on the other hand, understand the deep value of investing in your employees. They treat the company as a horizontal organization and value each individual’s point of view. Those organization are growing like crazy. Seriously. One of them is even on Inc.’s list of fasting-growing companies in the country. And it’s all because they treat their employees like the most loyal customers. In return, the employees are happy to come to work, be productive and take part in such an enthusiastic atmosphere. Sir Richard Branson was right: “Take care of your employees, and they’ll take care of your business.” 3. Underinvest in proper marketing. I know this part seems totally biased because I’m a marketing geek. But hear me out. In the age of endless information, marketing is the number one way to get your product noticed. It involves understanding your buyer, the problems your company solves, the problems it doesn’t solve, and its unique value proposition. I once spoke to a business with an innovative product. But the company had never invested in marketing. They thought that once they built the product, they’d build brand awareness and people would start buying. You know who else built brand awareness? TiVo. You know who’s stock has decreased 85 percent since reaching its peak over a decade ago? TiVo. The company spent so much time building a brand that they forgot to create their category. People understood what TiVo did, but they didn’t understand why they needed it. I can’t think of a single person I know who uses (or even owns) a TiVo. You know almost everyone I know has? Netflix. TiVo let you watch what you want, when you want. Netflix lets you watch what you want, when you want. But consumers didn’t know they wanted that until Netflix embarked on a rather brilliant marketing scheme of creating exclusive content. Now, we can’t live without it. More people are cutting the cord on cable and relying exclusively on streaming services like Netflix. People used to say they were going to “TiVo” something. People now say they’re going to “Netflix” and chill. Another note I need to make in this section is that I see a lot of companies leave marketing in the hands of people who are not competent. It’s as if marketing is viewed more as a side function, rather than an imperative driver of brand awareness, lead generation and customer acquisition. Hire marketers who can craft strategic campaigns and measure their results ― especially ones who can write well. When your messaging is clear, your sales go up. These are just my thoughts based on experiences I’ve had working with SMB companies. I’d love to hear your insights, too. Feel free to leave a comment below, or check out some of my favorite books on business and marketing.  By: Brianna Valleskey Marketing is much older than we think. Some people argue that the discipline emerged after the standardization of quality products halfway through the 20th century forced companies to find other ways to distinguish themselves from competitors (see: brand management). Others note that market research was first identified as a business activity in the early 1900s. A few even assert that marketing has been around since Gutenberg’s moveable type enabled the earliest print advertisements. These claims, however, depend highly on one’s definition of marketing. The American Marketing Association describes it as “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.” Quite a mouthful. Investopedia provides a more clean-cut explanation, where marketing is “everything a company does to acquire customers and maintain a relationship with them.” But my favorite comes from researchers and textbook authors Philip Kotler and Gary Armstrong: “Marketing is the social process by which individuals and organizations obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging value with others." In this sense, marketing began millions of years ago. Hundreds of millions. With plants. The Ancient Origins of Marketing As Hope Jahren explains in her book “Lab Girl,” the primary purpose of sex on planet earth exists is to mix the genes of two separate beings and produce a new individual with a gene code identical to neither parent. “Within this new mix of genes are unprecedented possibilities, old weaknesses eliminated, and new weaknesses that might even turn out to be strengths. This is the mechanism by which the wheels of evolution turn,” Jahren writes (poetically, I might add, which is a difficult feat in the realm of science writing). She goes on to describe that sex requires touch, where the living tissues of two separate individuals must come into contact and then attach. This is a problem for plants. Since they cannot move, many plants can (and still do) scatter their pollen on the wind in hopes that any amount will land on a female flower -- an incredibly inefficient process. So nature came up with a solution about 135 million years ago, biologist Dave Goulson describes in his book, “A Sting in the Tale: My Adventures with Bumblebees.” “Pollen is very nutritious. Some winged insects now began to feed upon it and before long some became specialists in eating pollen. Flying from plant to plant in search of their food, these insects accidentally carried pollen grains upon their bodies, trapped amongst hairs or in the joints between their segments. When the occasional pollen grain fell off the insect on to the female parts of a flower, that flower was pollinated, and so insects became the first pollinators, sex facilitators, for plants,” Goulson writes. “A mutualistic relationship had begun which was to change the appearance of the earth. Although much of the pollen was consumed by the insects, this was still a vast improvement for the plants compared to scattering their pollen to the wind.” A mutualistic relationship? That sounds like individuals and groups obtaining what they need and want through creating and exchanging value with others. Evolution & Adaptation Goulson offers even more: “Insects had to seek out the unimpressive brown or green flowers amongst the surrounding foliage. It was now to the advantage of plants to advertise the location of their flowers, so that they could be more quickly found and to attract insects away from their competitors. So began the longest marketing campaign in history, with the early water lilies and magnolias the first plants to evolve petals, conspicuously white against the forests of green.” Plants began marketing themselves millions of years before our first ancestors walked the planet. Our verdant, immobile fellow beings were the earth’s first marketers! It’s no wonder that studies show interacting with nature can increase creativity. And I’m sure there’s much more we could learn from nature. So the next time you need a little creative inspiration, talk a walk through a nearby park or conservatory. The fresh air, quick exercise and presence of the world’s most experienced marketers will surely spark something inside your mind. I also highly recommend you check out this excerpt of Goulson’s book that was published in Scientific American a few years back. Save the bees.

By: Brianna Valleskey